Dutch Immigrants and the Alamosa Disaster in Colorado

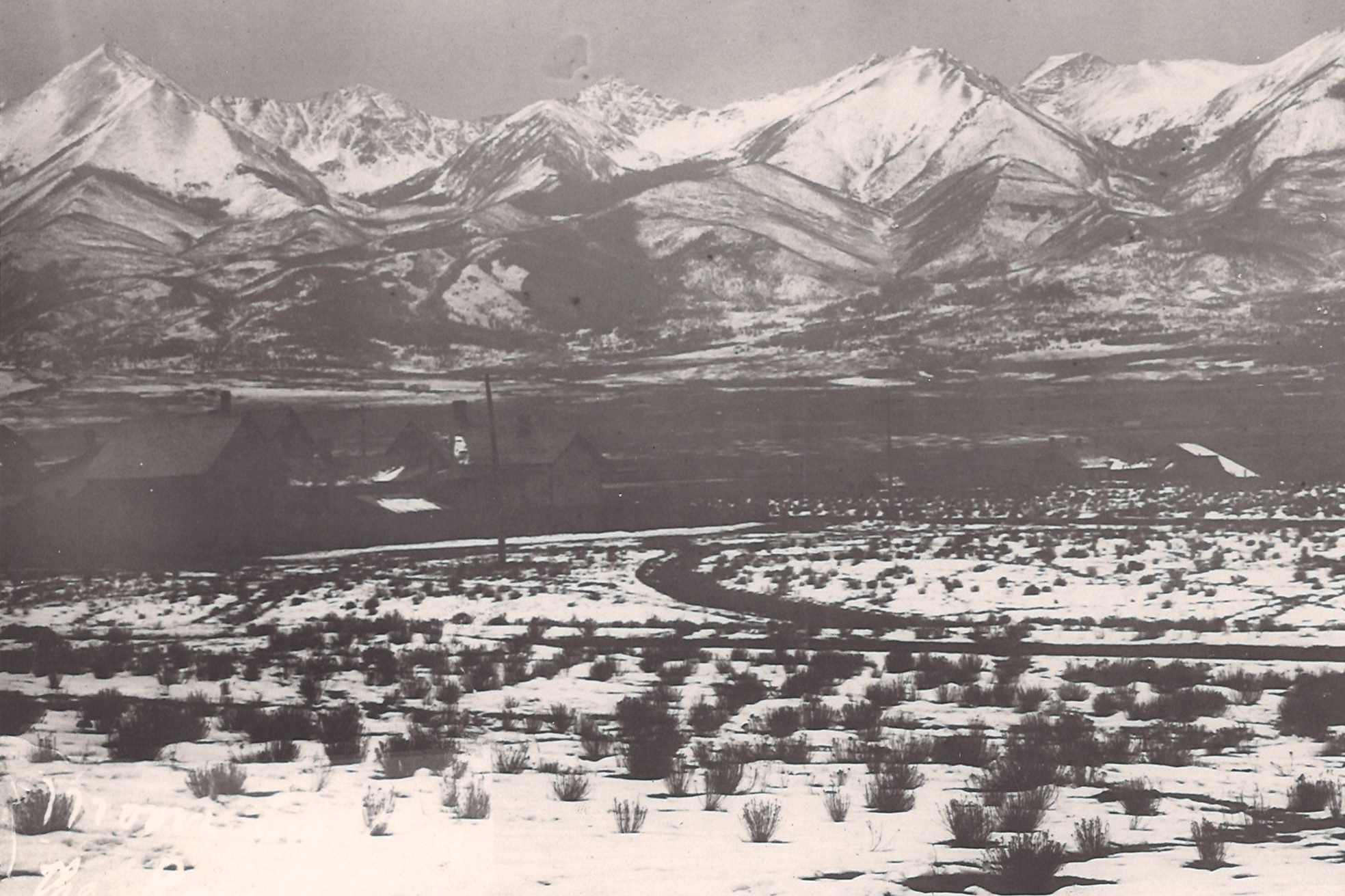

On November 30, 1892, on a train from Hoboken, NJ, to Alamosa, CO, Marinus Aalbers glanced at his wife and children sitting across from him in their seats. They had left the Netherlands 23 days ago and expected to arrive at their last stop in 20 minutes. He looked out the window at the Colorado countryside. They had passed mountains, flat lands, desert-like landscapes, and flowing rivers. Alamosa was in the San Luis Valley in south-central Colorado. The land here was truly varied and unique from what they knew in their homeland. Could this be the place they make their new home?

The pamphlet that guided them on this journey promised acres of land that were prepared for farming and suitable for the crops they were accustomed to growing. It described idyllic weather conditions year-round, beautiful houses for them to live in, and a life that would bring them wealth in excess if they should work hard for it.

Marinus desperately wanted this life for his two children. He hoped they would grow up comfortably and inherit land for their own use when old enough. He looked at them now, sitting across from him. They were sleeping for the first time today, having earlier watched out the window with wide eyes at a new world. America, Colorado, was the right choice, he thought. Leaving behind the depressed economy in the Netherlands, spending nearly their life savings on this trip, and hoping for a successful life in America was the right choice for this family.

[“Right-click” the images in the gallery and then click “View Image” for larger versions.]

After the train pulled up to the station in Alamosa, Marinus and his family exited to a crowd of locals, their mayor at the forefront. The mayor outlined the town’s excitement for their arrival, in a brief speech, saying he hoped that they would expand and enhance the community and population. Then the 28 Dutch families on the train from Hoboken were ushered into the Armory Hall where they were presented with a lavish meal and a moment of respite after their long journey. The population of Alamosa was roughly 1000 residents and the new Dutch families would add almost 250 souls with their 116 children, parents, and unmarried adults. Once the festivities died down, the families were brought to their new homes.

That’s when the first signs of trouble began for Marinus and the other families, the first indication that what they had been promised in the brochures may not be true.

The grand, furnished houses described in the brochure were in fact two poorly constructed wooden buildings. Each was 36 x 60 feet and two stories tall. The families attempted to settle in, but the “homes” were drafty and uncomfortable.

As the next few months trudged along, the families continually faced truths the brochures had not told them. The climate in the area, although promised to be the “Italy of Western North America”, was in fact far from it. The “mild” winter fell to thirty degrees below zero Fahrenheit, and the families struggled to stay warm in their ramshackle houses. At one point the adults ventured out to survey the land they were given. Despite being told it would be prepared for farming, much of it was still uncut prairie and the rest was unsuitable for agriculture due to the hilly terrain. Furthermore, they were told European crops would easily grow in the region, but they found the cold nights and short growing seasons ill-suited for many tender vegetables.

Their most pressing concern soon after their arrival, however, was the spread of disease in their compact living arrangements. Scarlet fever and diphtheria were two plagues common in the late 19th century. Children were especially vulnerable to these diseases, and Marinus and his wife feared for their children’s lives. Just weeks after they disembarked from their train, 11 of the immigrant children succumbed to disease.

With hopes of a new, prosperous lives dashed for Marinus and his fellow immigrants, one can only wonder who wrote the pamphlets that convinced them to uproot their lives in the first place?

It was a man named Albertus Zoutman, a recent Dutch immigrant himself. Intrigued by the healthy climate of Colorado, and the demand for new settlers, he set about creating one of the “boldest swindles” in history.

Zoutman wasted no time in building his land company. He arranged for thousands of dollars to be paid and promised in the future for the rights to fifteen thousand acres of land in Alamosa, Colorado. He enlisted several “well-known” men in the Netherlands to become leaders in the company. He also produced and distributed brochures from their headquarters in Utrecht, advertising the prospects of emigration to North America. His business became known as the “Immigration Company.” Immediately, he gained substantial interest from Dutch natives who were eager to leave their poor economic conditions in the Netherlands.

As the immigrants in Alamosa soon discovered, Zoutman was swindling them. He had not fully paid for the land they were to farm, and he provided no real plan for them once they began living there. Providing meals for the roughly two-hundred people there was difficult with an organized program. In Alamosa it was nearly impossible, given Zoutman’s neglect and mismanagement. When the immigrants complained about their living situation, the company showed them little sympathy.

The newly settled Dutch families were left with few options. Some chose to purchase land directly from the Empire Company, from which Zoutman supposedly had purchased the land they were to live on and farm. Eleven families moved away to establish their own farm, called the Empire Farm, while others remained loyal to Zoutman and his promises. The Immigration Company moved the remaining loyal families to a new settlement in Crook, in northwest Colorado, where they attempted to re-establish themselves.

Reality once again did not match Zoutman’s dazzling promises to the families. They found the population of 175 people in Crook ill-prepared to help the newcomers get settled. The immigrants lived in Union Pacific Railroad cars until they could find housing. Zoutman made more promises, about farming equipment and plans for the future, but his plans continued to fall through.

Eventually, the deceit of the Immigration Company caught up with it, and everything it owned was repossessed for non-payment. This left immigrants with starvation at their doorsteps, and no more wages or savings to lean on.

To the rescue came the Christian Reformed Church and the Reformed Church in America. Both denominations were accustomed to helping immigrants settle, whether in farm country or towns and cities. The immigrants moved on to parts of Iowa, where the promises, this time of the two churches, did not fall through.

It might have been predicted that the families who followed Zoutman’s promises from Alamosa to Crook failed in Colorado. The families at the Empire Farm also would fail. Poor crop yields and depressed wheat prices left the Empire Farm bankrupt. The CRC and RCA ultimately helped them resettle too. There were no crowds when they left. The remaining Alamosa colony immigrants, who had put their trust in Zoutman and the Immigration Company, and then had tried on their own in Colorado, picked up the pieces and tried to rebuild elsewhere, many prospering in their new surroundings.

The story of the Alamosa colony’s failure and the Zoutman swindle was not unusual in the American West of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Land companies like Zoutman’s often over-promised and under-delivered, sometimes out of incompetence, sometimes maliciously. And, whether immigrant or native-born, in colonies or on individual homesteads, farms often failed. If drought, hail, grasshoppers did not devastate a crop, low wheat prices and high interest rates might mean that families lost money on every bushel of wheat they sold.

The story on the Great Plains sometimes was success, sometimes failure, for family farms. It always was about endurance. (Reread the Little House on the Prairie novels with this point in mind!) Perhaps success was defined by farm families, and their communities, simply persisting in living the kind of life they wanted for themselves and their children.

Mabel Uhl is a student at Calvin University.

************

The photos in this post are courtesy of the Colorado Historical Society.

This post is based on a story in the print version of Origins. For the complete story, check out “The Alamosa Disaster,” by Peter De Klerk, in issue 4:1 (Spring 1986) of Origins: Historical Magazine of the Archives.

As a descendant of victims of the Alamosa disaster, it’s great to see the story uncovered once again! I’ve written the story from the perspective of my ancestors on my blog.

Thanks for the comments, April. I’ve heard from a variety of people about family connections.