A School, a House, and a New Purpose

In 1917 there was a major debate ongoing among Christian Reformed folk around Prospect Park, NJ. They needed to decide if it was time to establish a Christian high school.

Most people in the mainly blue-collar, immigrant community saw education beyond the basics of reading and math as an unaffordable luxury. As late as 1913 an effort to start a high school to train teachers for the Dutch Reformed elementary schools failed after only one student enrolled.

Things changed on Labor Day in 1917. Rev. Walter Heeres of Prospect Park Christian Reformed Church (CRC) ignited support for a Christian high school when he offered to sell his car to fund the school if others in the community would join him in making sacrifices. On the very same day two years later, September 3, the new Dutch Reformed high school welcomed its first class of 18 students.

Why did the plan to start the school succeed in 1917 where the attempt in 1913 had failed?

For one thing, only four years later, in 1917, more and more graduates from nearby Christian elementary schools were going to public high schools. For many pious CRC folk, this wouldn’t do. If the students were going to high school, they should have access to a school founded on properly-Reformed Christian principles.

With this thought in mind, Christian elemnatary school officials and ministers decided it was time to try again. So, when Rev. Heeres made his call to action in 1917, people listened. Supporters called for a community-wide meeting in February 1918 to explore the idea.

When the time came, supporters of the plan packed a YMCA meeting room. Some 300 people came. Rev. J. Vander Mey, a CRC pastor and the financial agent of Calvin College, took the stage. He declared that Christian education did not end at age 14 but was a lifelong endeavor, perhaps trying to encourage support for Calvin College as well as the new high school.

Sixty attendees responded to the call by forming a school association. Within a year they had elected a school board and began planning to open by fall 1919. But despite the progress, resources remained a problem.

The board borrowed a classroom from the N. 4th Street Christian School, and Gerhardus Bos accepted the job of principal. He took only half the offered salary, but the new school remained in serious trouble. At the start of the school year, the board had only $628 on hand, a far cry from the $2,000 needed to fully fund operations for the year.

The school had one full-time teacher, a principal, and a looming financial crisis. Despite these dire straits the first 18 students began studying Latin, math, and English, along with theology and other subjects approved by Calvin College. The faith of their parents—in the school, in Christian education, and in the God they worshipped—paid off. As classes picked up, so too did donations to the association. By the next summer, in 1920, the school was fully funded with a little bit of cash left over.

The school applied for accreditation by the state board of education towards the end of 1922. An inspector came to examine the building and the curriculum and to ensure that the largely Dutch school did not contain any element seeking the overthrow of the government. The school passed the test.

In 1923 the first class graduated from the recently christened Eastern Academy. The name was inspired by Western Academy in Hull, Iowa, from which the board first got approval before using the name. Many of the graduates became teachers, and a few went on to college.

Success presented a challenge, however. Eastern Academy already had outgrown its rooms on N. 4th Street. The school association began a search for a new home for the school.

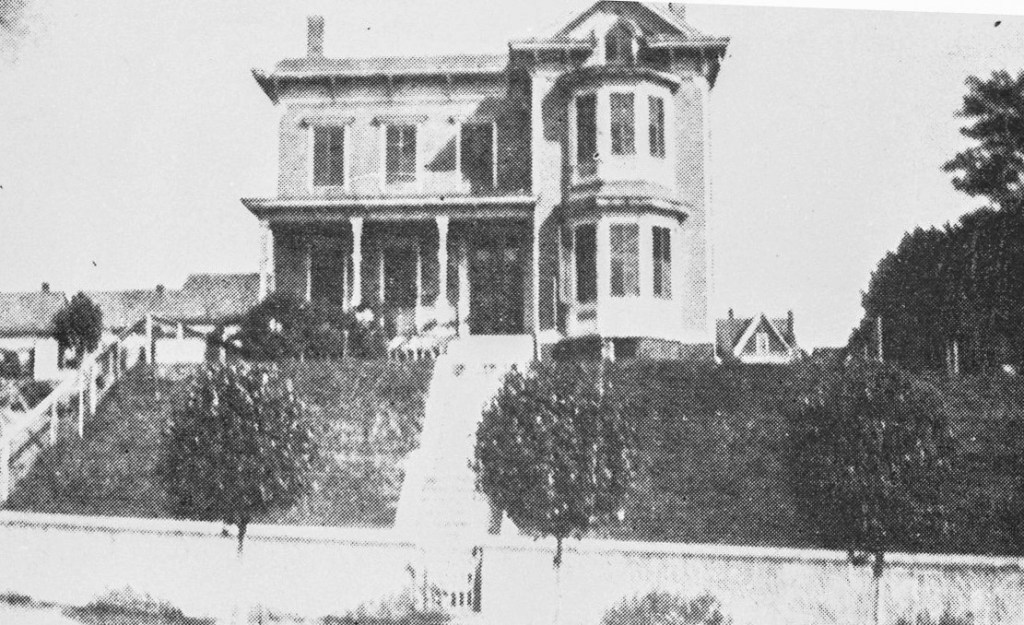

The building they found was a large home on 7th Street referred to by locals as the Stansbury Estate. Little is written about its last inhabitants, John and Rachel Stansbury. They were influential members of the community and Rachel’s father had once owned most of the land of Prospect Park. Fittingly, one of their relatives had founded Prospect Park’s first school board.

In 1924 the board purchased the estate for $13,000. It spent another $8,000 converting the house into a school. When the renovations finished, the students gathered the supplies from the 4th Street facility and marched across town to the new building

The school board considered its next move only two years later, as growth at the Eastern Academy continued steadily. It launched the “$200,000 Campaign” in March 1926 to fund the construction of a large brick extension to the Stansbury house. Excitement in the Dutch Reformed community buzzed while the line on the large “thermometer” in a local barbershop climbed upwards to mark progress.

Progress eventually stalled, and the board had to settle for a more economical goal of $100,000. (Calvin College and Rev. Vander Mey similarly had to settle in their fundraising campaign around this time.) Construction began. In September 1928, the community dedicated the new building. Prospect Park Mayor Peter Hook and former Calvin College President Rev. J. J. Hiemenga—who would serve as president of Eastern Academy’s board starting the next year—attended the event.

By the 1980s, Eastern Academy and the 4th Street Elementary School had moved out of Prospect Park and consolidated as Eastern Christian School. Fewer students came from Paterson and Prospect Park by then, and more came from towns such as North Haledon, Wyckoff, and Midland Park to the north, where Eastern’s new campuses could be found.

While a lot has changed in the community around 7th Street, some things remain the same. Today the old Eastern Academy building is home to Al Hikmah Elementary School, where a newer immigrant community continues to use it for the purpose of private religious education. Its mission is to “simultaneously” instill “Islamic Character while ranking in the top decile in STEM and the Arts.”

***

Matt Vander Wall is a history major and a student assistant in Heritage Hall at Calvin University.