Architecture and Philosophy on Calvin’s Campus

This blog post summarizes, excerpts, and links to a story done by Chimes, the student newspaper at Calvin University. The Chimes story is based on a summer research project done by student researchers Gabby Freshly and Natalie Sytsma and supervised by art history professor Craig Hanson. The project was funded by Calvin’s McGregor program: “Calvin’s Knollcrest Campus: A Fifty-Year Celebration, 1973-2023.”

[There’s a link to the story below, after some Fyfe drawings, photos of the campus, a summary of the Chimes story, and an excerpt from it.]

The Knollcrest campus of Calvin University and Calvin Theological Seminary are a product of a philosophy of Christian education and the aesthetic vision of William Fyfe and his famous mentor Frank Lloyd Wright. College president William Spoelhof gave Fyfe homework–essays and books by Calvin faculty describing the school’s approach to higher education. Fyfe eventually believed that the Knollcrest campus was the finest work he had done in his career. The project restored his faith in higher education.

The cover image for this post is a conceptual drawing down by Fyfe’s team in 1959, as they were working out this philosophy, aesthetic, and vision and imagining the shape and look of the projected campus.

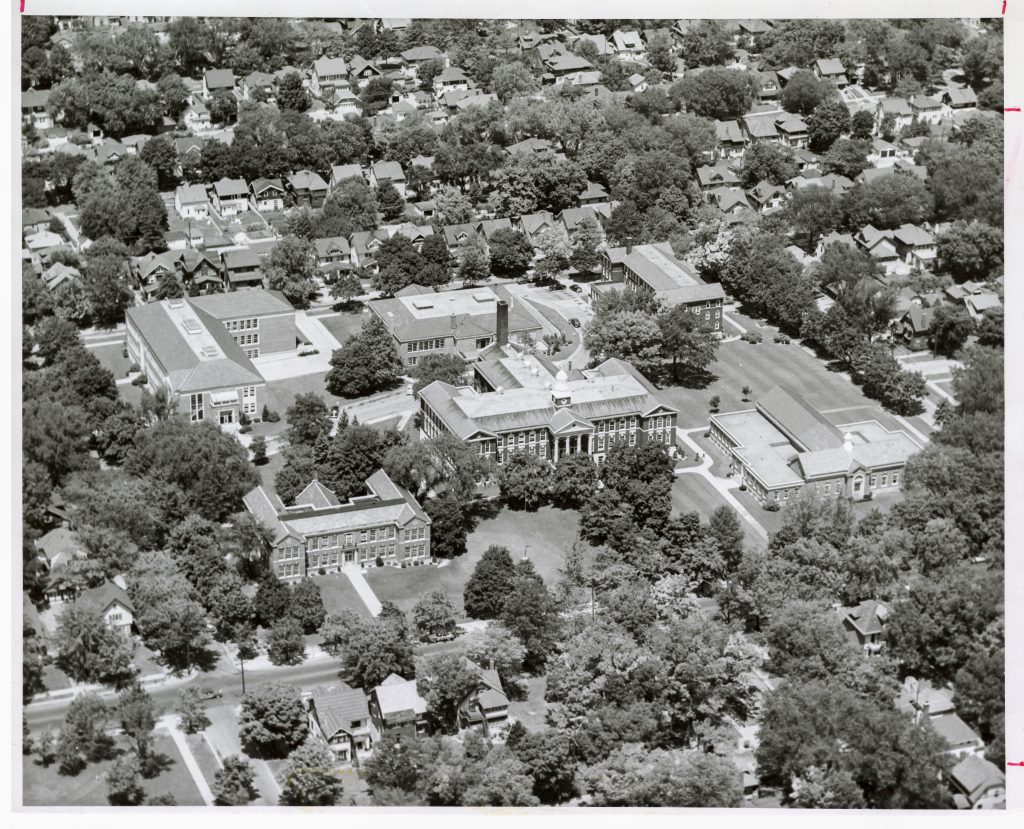

The context was Calvin College and Seminary outgrowing the old “Franklin” campus, as student numbers rose from several hundred students in the mid-1940s to about 3000 by 1960. The whole of higher education in North America was booming in the two decades after World War II, in a “golden age” for higher education. Calvin purchased the Knollcrest farm in the 1950s and the college and seminary built the campus and moved into it gradually during the 1960s and early 1970s. Calvin went from being a school in the city to one in suburbs.

Here’s an early part of the Chimes story:

In 1956, Calvin College — under the leadership of President William Spoelhof — purchased Knollcrest farm. Calvin’s campus at the time was located on Franklin Street, in the heart of Grand Rapids. But after World War II, the college had experienced a period of intense growth — so much growth that the Franklin campus began to feel claustrophobic.

“Spoelhof was projecting in the future that Calvin’s intense growth would continue,” said art history professor Craig Hanson, who conducted research on Calvin’s architecture this past summer. Knollcrest farm — the site of Calvin’s current campus — offered ample opportunity for expansion.

Spoelhof turned to architecture firm Perkins and Will, which Hanson described as “the most progressive architects for education,” to design and build the new campus.

“Spoelhof goes to [Perkins and Will] with the intention to produce a modern campus,” said Hanson. “I take Spoelhof’s aim, above all, to be cultural engagement — an assertion that, whatever is going to happen on this campus, it will matter in the present, not in the past. And, implicitly, it will matter in the future.”

The firm assigned architect William Fyfe, a student of Frank Lloyd Wright, to the project.

Fyfe was a proponent of Prairie style architecture — a style focused on the integration of buildings and landscape via elements like flat roofs and natural colors. “The buildings aren’t supposed to dominate,” said Gabrielle Freshly, one of Hanson’s student researchers. Instead, “they’re supposed to look like they’re springing up.”

The Chimes article goes on to take the story of the Calvin campus into the present. It describes the social and cultural context of the “master plan” for the college (now university) and seminary campus, in a time of transition for the two institutions and the Christian Reformed Church, all serving a long-time immigrant denomination that had recently Americanized and become more middle class and prosperous (along with many other post-war Americans).

The Chimes authors take the story into the present, examining how the campus has evolved in the 50 years since it was first built–as its curriculum grew (e.g., adding a variety of professional and graduate programs) and its student body, staff, and faculty became more religiously, ethnically, and racially diverse.

How do the philosophy, aesthetic, and values in the original master plan look today? What tensions and challenges mark the campus today? What of Fyfe’s vision endured? What has changed?

Check out the Chimes story for more details and analysis: Katie Rosendale and Abigail Ham, “Calvin’s architecture and identity have evolved, and continue to evolve, side by side.”

***

William Katerberg is a professor of history and curator of Heritage Hall at Calvin University.

The two photos, of course, are E.G. Boer and Wiebe Boer. First and twelfth presidents of Calvin University, as I’ve told the story.